When talking about the rise of Prestige TV, there is one series almost universally noted as the first to get it right. David Chase’s grounded drama about a mob boss seeking therapy was not a comedy like Analyze This. While The Sopranos was unique from the beginning, the fifth episode of the first season proved it was not just a “mafia show.” Instead, it was an artful, clever series about a dysfunctional family that just happened to be in the organized crime business.

Originally, The Sopranos was going to be a feature film from Chase that applied his own family dynamics, particularly with his mother, to a mobster. He was in therapy at the time, and thus that element was added to the story. The film eventually evolved into a television series, and The Sopranos went on to highlight how, despite their money and violence, they were mostly pathetic and disturbed. However, Season 1, Episode 5, “College” shows The Sopranos was on another level creatively than any mafia story before or, arguably, since.

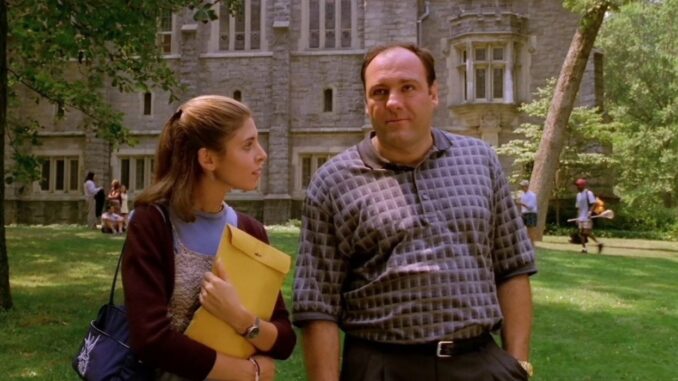

Tony and Meadow’s Conversation Exemplifies The Sopranos’ Family Theme

The title, “College,” is drawn from Tony and Meadow’s story, as he takes her around Maine in a rented Crown Victoria to visit colleges. The first scene implies during the trip, Tony and Meadow have spent almost all their time together. Later, by chance, Tony sees a former mafia associate who became an FBI informant and relocated in Witness Protection. Before he’s even introduced, Meadow confronts her father with a question that most organized crime stories would leave to subtext. As they drive along to the next campus, Meadow asks him flat out if Tony “is in the Mafia.”

Tony responds with what seems like a rote denial based on incredulousness and offense. He tells her “there is no mafia.” Meadow pushes back, confronting him about his strange hours, constant police raids and finding guns and money stashed around the house. She even confesses her peers at school “think it’s neat.” While Tony continues to mostly deny it, he admits to her that “some” of his income “comes from illegal gambling and whatnot.” When he tries to drift the conversation back to things like prejudice against Italian Americans, Meadow tells him to not “start mealy-mouthing.”

This scene, and the rest of the episode, balances Meadow’s obvious love for her father, with the reality staring her in the face. While this remains a theme throughout the show, she’s most moved that he was honest, even if not telling the whole truth. She tells him she appreciates the honesty in their relationship. Then, throughout the rest of the episode, Tony lies to her repeatedly. Despite the legal reasons to not share the details, it’s clear to Tony that murdering some guy for testifying wouldn’t be nearly as “neat” as running numbers and illegal poker games.

From the Kids to the Adults, ‘College’ Shows the Soprano Family at Their Worst

Throughout the run of The Sopranos, Tony is shown to be a strict father, largely because of his sociopathic tendencies and his own abusive upbringing. However, on this college tour, Meadow is left alone and gets drunk, despite Tony’s specific instructions not to drink. Yet, this opportunity only arises because Tony needs some time to investigate whether he actually saw Fabian “Febby” Petrulio, a made man who turned state’s evidence a decade ago. Tony has no specific grudge against Febby, his only motivation to kill him is that he broke the omertà.

Meadow is able to get blind drunk, and Tony shows her nothing but compassion. However, he uses this to gaslight his daughter, blaming her intoxication for accurately saying he was running outside to a payphone all night. Back at the Soprano household, Anthony, Jr. is mostly absent for the episode. Given how later episodes depicted his rebellious disregard for the rules, it’s fair to assume he wasn’t having the simple sleepover his mother thought.

Since Carmela has the house to herself, she entertains Father Intintola who stops by because of a bad storm. In the episode, the priest asks if he’s considered a “schnorer,” which he says is a Yiddish world for a person who invites themselves to eat others’ food. He also brings a romantic movie to watch, implying he and Carmela have done this before. The entire storyline has deeply intimate undertones. It’s a classic affair and seduction story, yet “College” replaces physical intimacy with Catholic sacraments.

How The Sopranos Brilliantly Conceptualized Carmela’s Approach to Infidelity

While Intintola is a significant character, this part of the story is all about Carmela coming to grips with the same subject Meadow broached. Specifically, her introspection is triggered when Dr. Melfi calls to reschedule Tony’s therapy appointment. Supportive of her husband seeking professional help, Tony lied (arguably by omission) about his therapist being a woman. Even though the relationship was purely professional, Carmela assumes Tony is cheating on her again. In an emotionally and spiritually vulnerable place, Intintola’s visit is Carmela’s version of infidelity.

There is physical attraction, but the intimacy is represented not by sex, but rather the rituals of the very faith that won’t allow her to leave him. This culminates in the holiest of Catholic sacraments: communion. Intintola has the kit he uses to visit the sick and elderly, so he performs the sacrament for her. Yet, since Carmela is in her pajamas and the setting is her living room and not a church, the ritual is incredibly suggestive. So much so that, the scene ends with them holding each other until they fall asleep together on the floor. Just before this, Intintola performs another sacrament: confession.

Sitting back-to-back on the couch, Carmela tearfully confesses. She tells the priest what she knows to be true about Tony’s place in the mafia. She breaks the same omertà that Febby dies for, though in a less legally-troubling sense. She also confesses what she suspects to be true: that Tony has killed people. This is especially poignant because Tony leaves his daughter alone in strange places, so that he can do just that. Carmela’s scenes are some of the most brilliantly constructed in the series, and possibly why Chase himself says this is his favorite episode, according to a Season 4 commentary track.

‘College’ Ends with ‘Rat’ Being ‘Whacked,’ but It’s Not About the Murder

The study of this family, the importance of honesty and the lies Tony tells proved The Sopranos was going to elevate the already-oversaturated gangster genre. While a mob boss whacks a rat in this story, what makes it so unique is that it’s not what the story is really about. Instead, it’s how Meadow observes Tony using the payphone, disappearing for hours in this tiny town and the wound on his hand from garroting Febby to death. The murder of Fabian Petrulio is not about “mob honor.” It’s there to highlight for viewers how easily Tony erodes the evolution of his and Meadow’s relationship with his “honesty.”

If “College” was a feature film or an episode of any series but The Sopranos, one scene would’ve played out differently. Febby is aware Tony is in town, and he tracks him to their hotel. He has a pistol trailed on the man who would kill him as Tony laughingly helps a drunk Meadow to bed. Any other storyteller would’ve had him take the shot anyway, if only to add some old-fashioned “mob action.” Earlier, Tony stalked Febby at his house, learning he has a child of his own. Seeing Tony with Meadow humanized him for Fabian, whereas Tony probably never gave Febby’s child a second thought.

Similarly, Carmela’s story subverts expectations in ways other entries in the genre might not. “College” lays bare her conflict with her life, through tears and justification. Instead of kissing or even sleeping with the priest, they share an almost chaste intimacy punctuated by holy sacraments. Audiences are left to wonder when, if ever, Tony and Carmela dozed off together on the floor in each other’s embrace. However one feels about the ending of The Sopranos, there is no denying David Chase delivered clever, artistic television from the beginning.