All in the Family was the first show to honestly look at the cultural upheavals of 1960s America. TV would never be the same.

When CBS first aired All in the Family on January 12, 1971, it irrevocably changed television. After an unstable first season and struggling to find an audience, the show took off, reaching No. 1 in the ratings for five consecutive years, an unprecedented record at the time. All in the Family has captured national attention on a level almost unimaginable in today’s fragmented entertainment landscape. Archie Bunker’s slogans—choking, stubborn, and dingbat—have all become national shorthand. Scholars have seriously debated whether the show punctured or encouraged bigotry.

Its success not only helped elevate The Mary Tyler Moore Show, M*A*S*H, and other great topical comedies of the early 1970s, but also reinforced the idea that television had could be used to meaningfully comment on the society around it—an idea that the networks uniformly rejected during the upheavals of the 1960s. That legacy—the determination to connect the media to the moment — echoed through shows as diverse as Fleabag, Atlanta, Breaking Bad, The Wire and countless others. The night that CBS first aired All in the Family was the first step on the road toward Peak TV that we are experiencing today.

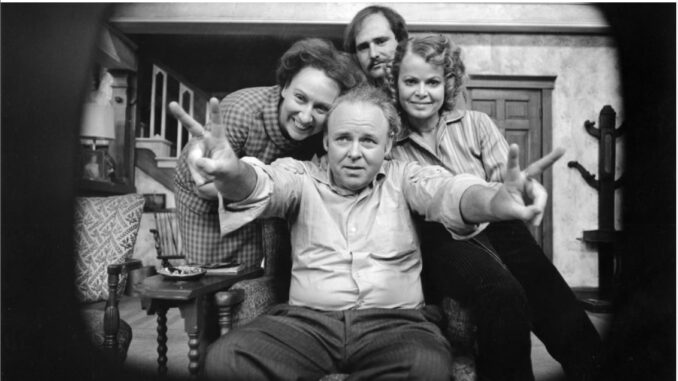

All in the Family condensed the “generation gap” of the 1960s into a single living room. It pitted Mike Stivic, a long-haired liberal, and his wife, the bubbly Gloria, against Gloria’s father, Archie Bunker, a reactionary bigot and dock worker who loved Richard Nixon — as Edith, the dashing but benevolent wife and mother, witnesses. Presented by a stellar cast and invigorated by excellent writing and direction, the series became a television milestone, widely hailed as one of the best shows and most influential ever.

However, at first, All in the Family’s airing was a miracle. Before CBS bought it, ABC turned it down twice. And before All in the Family, shows that tried to gain more relevance mostly failed, mainly because they were filled with too many good intentions to attract audiences. That All in the Family not only stayed on the air but prospered was the result of two men: Norman Lear, its staunchly liberal creator, and Robert D. Wood, the conservative president of CBS , who put it on the schedule. That act revolutionized television, but neither of them were revolutionaries.