The South is freighted territory, thick with ghosts and nonsense, and performative professional Southerners who regularly lie to strangers, friends and sometimes themselves.

I was born in and have lived most of my life in states that were part of the Confederacy, but understand that in an internet-connected America pimpled with box stores and chain restaurants where everyone watches Netflix or Hulu or CNN or Fox, one can slip on a Southern identity like one slips on a seersucker suit.

While affected folkiness can be an effective tactic for anyone with a public-facing platform, be they Lonesome Rhodes or Sheriff Andy Taylor, it can also grate. Professional Southerners proliferate in certain businesses (including this one), injecting sentimentality and schmaltz and obscuring the common though complex humanity of people who happen to live below the Mason-Dixon line. “Southern” is a suspect adjective one should never apply to one’s own work. It is as much a ghetto-izer as it is a sales pitch.

That said, I do not hate Southern movies. (As Quentin Compson says, “I don’t. I don’t.”)

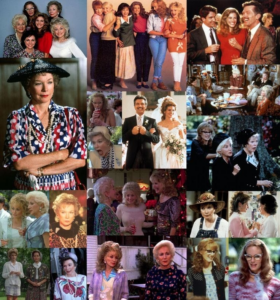

I dislike movies that present an idealized or reductive view of the South and the people who live here. Movies like “The Help” and “Driving Miss Daisy” and “Green Book.”I used to loathe “Steel Magnolias,” the Herbert Ross movie returning to theaters briefly this week, courtesy of Fantom Events and participating theaters, in celebration of its 35th anniversary. I remember that when the movie was released in 1989, my reaction was so extreme that I decided not to write a review of it, instead farming the chore out to a female freelancer who concluded the film didn’t like men and was clueless about the South.

As I remember, my main objection to “Steel Magnolias” was a moral one. I understood it was inspired by a true story, the death of playwright Robert Harling’s younger sister Susan in 1985 from complications arising form her diabetes, and I found the idea ghoulish and exploitative. (One of the advertising tag lines used to market the movie was that it was “the funniest movie to make you cry.”)

Aside from that, I thought most of the Southern accents attempted in the movie were atrocious. Julia Roberts, from the Atlanta suburb of Smyrna, Ga., was the worst offender, adopting a dropped-R drawl that sounds more like Scarlett O’Hara than anyone from northwest Louisiana. (It has been reported that director Ross insisted on the accent.) Dolly Parton used her natural Appalachian accent, which was fine but out of place for the character. Sally Field’s tended to come and go — only Shirley MacLaine (a Richmond, Va., native) maintained a credible and consistent accent throughout.I also bristled at the affected Southernness of the movie’s characters; I thought they and the Natchitoches, La., the film evoked (in the movie the town is referred to as “Chinquapin”) were phony. Despite some fine performances, especially by MacLaine and Olympia Dukakis, nothing about “Steel Magnolias” felt honest (which is not the same thing as true). While the film was set in the ’80s, in some ways it feels as though it’s playing out in some idealized ’50s village.

While I didn’t grow up there like Harling did, I did know the town. I briefly considered going to college there, to Northwestern State University (now officially known as Northwestern State University of Louisiana). I remember they used to have the state high school academic fair there; after taking your calculus or French exam you could buy one of their famous meat pies and walk along the river.

Natchitoches is an odd town; though it’s technically situated in northwest Louisiana (actually it’s as close to the geographic center of the state as the Texas border) it doesn’t feel as influenced by east Texas as the rest of northwest Louisiana. This is in part because it was established in 1714 by Canadian explorer Louis Juchereau de St. Denis as the oldest permanent European settlement within the borders of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, and settled by French traders and Canadian immigrants; by Creoles. Natchitoches looks and feels a lot more like New Orleans than Shreveport.

Up until the 1830s, when the Red River shifted course and left the city with an oxbow lake rather than a direct conduit to the Mississippi, Natchitoches was an important port, with east Texas cotton planters using it to ship their product to New Orleans.

It has been used in several movies — one of the nearby cotton plantations was a primary location in “12 Years a Slave” (2013). Reese Witherspoon made her film debut as a 14-year-old in Robert Mulligan’s 1991 film “Man in the Moon,” that was shot in and around the city.

But Chinquapin felt like the sort of Southern town that Disney’s imagineers might have conjured for Epcot Center. It felt gauzy and backlit, tenderly distressed in some places but not genuinely scruffy, a generic Thomas Kinkade twink