Al Pacino on His Legendary Roles

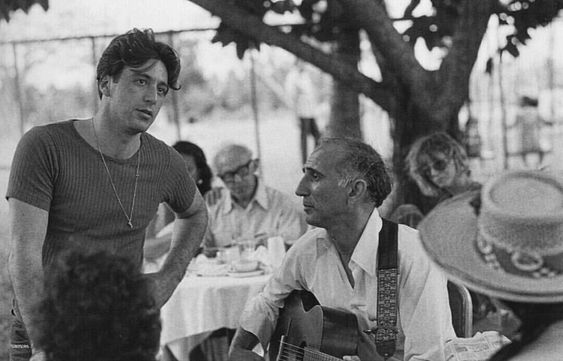

It’s tempting to call him “the inimitable Al Pacino,” although he is the most imitated actor in the world. There are, after all, two categories of imitation: impersonation (“Say hello to my le’el friend!” “Hoo-ah!”) and emulation. Emulating Pacino would mean not just bounding into a field of psychological land mines but identifying each one and purposely jumping on top of it. Some, including Johnny Depp, of all people, think he’s mad. Most see the larger wisdom in his design for living and working — and also think he’s mad. The exception is Pacino, who struggles not to think of himself at all so as to concentrate on the next task, the next land mine. For him, there is no other way. If further validation were needed, he could point to a 31-film retrospective in the place he came of age. It’s called “Pacino’s Way.”

He is thrilled that “Pacino’s Way” was proposed by the folks at the Quad Cinema in the Village. On the phone from L.A. in three rambling, absolutely delightful hours, Pacino, now 77, effuses over the years (beginning at 16, when he dropped out of the High School of the Performing Arts) in which he roamed the neighborhood, sometimes homeless and sleeping on the stages of small theaters, moving from production to production, and meeting, in a bar at age 17, his mentor, the late Charlie Laughton (not the famous one), who brought him to the Herbert Berghof Studio.

“I was just stunned by the fact that the Quad offered this to me,” he says. “I immediately crashed on when I was a kid down there. Sometimes you feel closer to what you were than you expected.”

The retrospective (it begins March 14) features most of the biggies: the first two Godfather films (he thinks the third was a mistake), Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Scarface, Scent of a Woman, Heat, as well as — surprisingly, at Pacino’s request — his most formidable bombs, Bobby Deerfield and Revolution.

Equally vital for him are the movies he directed, like the rarely seen Chinese Coffee (based on a play) and two relatively recent films in New York premieres: a spare, stylized version of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé he stars in with Jessica Chastain — he’d hoped the film would help launch her career but she did pretty well without it — and Wilde Salomé, a documentary about his relationship with the play. In it, he reveals the often-wayward process of putting together the earlier film and a concurrent L.A. stage production. The documentary isn’t as exhilarating as his 1996 free-form seminar, Looking for Richard, a kind of goofy master’s thesis on the Bard, the hunchbacked king, and the nature of his theatrical obsessions. But it’s full of enjoyably bizarre episodes, like the one in which Pacino throws a lavish cocktail party so that an unprepared, rather confused Chastain can improvise. Wilde Salomé illuminates the space where Pacino is happiest: the experimental theatrical milieu in which, 50 years ago, he found his voice.

Pacino grew up poor in the Bronx, a wild kid with no dad and a fragile working mother, who raised him with the help of his grandparents. School — even the Fame school — couldn’t hold his attention. In the ’60s, his world snapped into focus after he met Laughton and gurus like the Living Theatre’s Julian Beck and Judith Malina (who’d play his mother in Dog Day Afternoon), and, of course, Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio. “I was doing Creditors at the Actors’ Gallery and sleeping on the stage I performed on, and so I’d meet Charlie at Washington Square Park and we’d have hot chocolate and coffee in the freezing cold. It was great. It was next to NYU … I so flash on the Village there. I’ve lived all over the city, but the Village at that period of my life is the memory that seems to keep — it repeats itself. It makes me feel good to think about that time.”