Fifty years later, ‘The Godfather’ remains a landmark in cinematic history

When Francis Ford Coppola first glanced through a novel by Mario Puzo, he thought it “a rather sensational, sleazy crime novel”. Not long after, he made The Godfather, one of the greatest movies ever made.

There are not many candidates for best film ever made: Battleship Potemkin (Sergei Eisenstein), Citizen Kane (Orson Welles), Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray), Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa)… the making of The Godfather was a landmark in cinematic history because of its depiction of the Mafia, its drama, sweep, exploration of power and illegality, but also its rendering in all its complexity of a community, a family, and of the structure of American society.

While the focus here is on the movie, it is inseparable from its counterparts, the second and third episodes of the saga, which together make up the kind of span covered by the miniseries of today.

The Committee on Organized Crime was convened in the US in 1950, with televised hearings, and another committee in 1963 looking into organised crime also received nationwide attention. Paramount studio boss Bob Evans was convinced interest in the Mafia was growing. Puzo, heavily in debt, submitted 60 rumpled pages to Evans, who bought the rights for $12,500 (more or less R215,000) to turn it into a movie.

Earlier treatments of the topic had failed at the box office because, Evans thought, they were not made by Italian-Americans. He was convinced the movie “must be ethnic to the core. [Y]ou must smell the spaghetti.”

Coppola, 30 at the time, had written the Oscar-winning screenplay for Patton, and just made a decent film, The Rain People, which was a box office failure. He owed the studio money but he was reluctant to make a movie that glorified violence, but producer Albert Duffy convinced him and he took on the project.

He reread the novel, this time finding it was “the story of a family, this father and his sons; and I thought it was a terrific story, if you could cut out all the other stuff.”

Aspects of production

Puzo’s novel was a bestseller, selling more copies than the Bible, but he was finding it difficult to turn it into a movie script, so he got help from Coppola.

Filmed by Gordon Willis, the movie features scenes of every kind: assassinations, funerals, sick beds, baptisms, weddings, a blood-splattered horse’s head in satin sheets, all shot in a variety of shades and lighting. Darkness is deployed as frequently as light, submerging the viewer in the play of light and shade. Willis was at odds with Coppola about how the director wanted him to render the drama, but eventually came round to his sensibility.

The music was at times moody and dark, but also light and frivolous. Nino Rota had written the music for a string of Fellini movies, and was an accomplished and innovative artist of musical soundscapes.

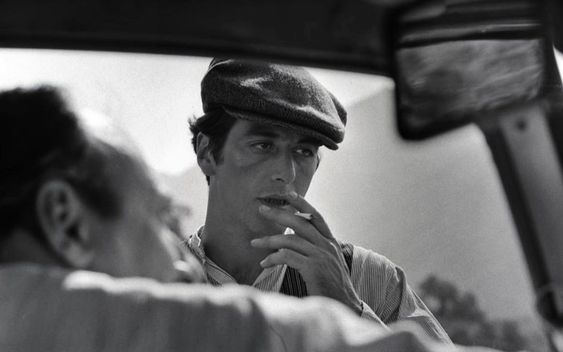

The cast contributed to the film’s greatness: Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, Dianne Keaton, Robert Duval and James Caan were the best known. Brando appeared after a lull in his career, which the film resuscitated. Pacino played the main character with an intensity that is frightening, and Keaton appeared in one of her most serious roles.

The remaining cast is a wonderful mix of characters, exuding an authentic Italian, Sicilian flavour. Oddly shaped men and women, with distinctive faces, gaits, ways of being; this was a world far, far from the superficial poise of smiley Hollywood optimism.

Drama in the Godfather’s household

Everyone knows, by now, the story: the reign of the godfather, his gradual demise as Mafia families engage in a struggle for dominance, and the accession of his third son to the seat of power.

The Mafiosi are gangsters, but they are more than a gang. Besides being larger and having more resources, they are bound by codes of honour and loyalty, a veritable object of anthropology. Nevertheless they are parasites, living off protection money, gambling, prostitution and drug running. And yet Vito Corleone accumulates respect and power by killing other parasites. He refuses to get involved in drug running, for moral as well as pragmatic reasons, initiating a mob war.

“I believe in America, America has made my fortune,” are the first words spoken in the movie’s wedding scene, with an undertaker pleading with the Godfather for justice for the two men who raped his daughter. “I want them dead,” he says. “You didn’t ask with respect, you don’t offer friendship. You ask me to murder for money? What have I done to deserve such disrespect?” The Don agrees to administer justice after the undertaker recognises him as “Godfather”. He is able to right wrongs the justice system is unable to.