How ‘The Sopranos’ defied the odds — and the rules of TV — to become a hit

In 1999, during its first season on HBO, “The Sopranos” was the biggest TV show in the world.

It didn’t have the largest audience — its ratings were still dwarfed by network hits like “ER” and “Friends” —but it had cultural cachet.

The dark, sometimes comic tale of a mob boss from New Jersey was omnipresent, discussed and debated everywhere from The New York Times to the “Tonight Show to every water cooler in the country.

It was so critically beloved that during its first year, “Saturday Night Live” didn’t parody the show itself but the review.

“The Sopranos will one day replace oxygen as the thing we breathe in order to stay alive,” read a fake critical assessment.

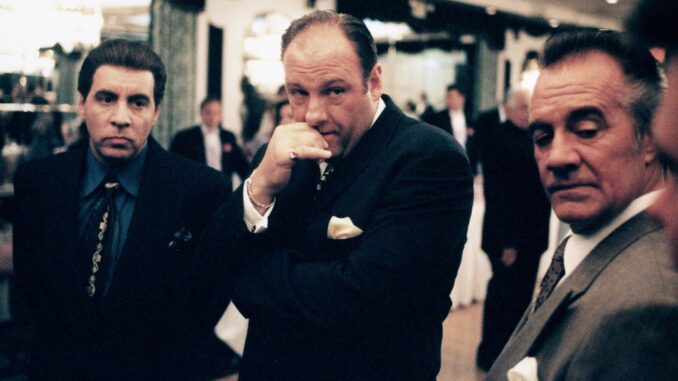

But the series at the forefront of a golden age in television was chaos behind the scenes, with a depressed, vindictive creator; an alcoholic leading man with self-esteem issues; and a struggling cable company that invested its future in a show about, as star James Gandolfini once described it, “a bunch of fat guys from Jersey.”

Nobody involved in “The Sopranos,” from creator David Chase to any of the actors, thought it would survive.

“It just violated too many do’s and don’ts, even for pay cable,” writes Peter Biskind in his new book, “Pandora’s Box: How Guts, Guile, and Greed Upended TV” (William Morrow).

Chris Albrecht, the former chairman and CEO of HBO, once put it after watching the pilot, “A gangster with existential crises wading in the pool with ducks? Not the most obvious thing for HBO to make their big bet on.”

The success of “The Sopranos” really came down to one man: David Chase, who was already in his mid-50s when the series premiered. In middle age, he was determined “to write a script in which the material wasn’t pre -chewed for viewers,” writes Biskind.

As Chase explained to the author, “On network, everybody says exactly what they’re thinking at all times. I wanted my characters to be telling lies.” He also didn’t want “huggable moments,” where characters learned something before the end of each episode. And above all, he didn’t want it to resemble anything else on TV. “I wanted to make a little movie every week,” he says in the book. Chase’s disdain for mainstream TV was apparent. “There are things in “The Sopranos” that are just ‘f–k you’ to network TV,” former staff writer Matthew Weiner tells Biskind.

A native of Clifton, NJ, Chase grew up in an abusive household — his mother once threatened to blind him with a fork because he wanted a Hammond organ — and struggled with depression. When asked if he ever contemplated suicide as a teen, Chase answered , “Well, doesn’t everybody?”

His dark thoughts only got worse when he graduated from Stanford and moved to Hollywood in the ’70s with dreams of writing feature films like his idol Federico Fellini. Instead, he ended up in TV, a medium he despised, writing formulaic scripts for shows like “The Rockford Files.”

He developed a “reputation for being too dark,” according to Chase.

Larry Konner, a “Sopranos” writer and long-time friend of the writer-producer, says Chase became known in the TV industry as a “good writer, but what’s going on in his brain, we don’t want to be part of.”

Chase felt as out of step with the Hollywood mainstream as they did with him.

He recalls watching the Julia Roberts movie “Pretty Woman” during a cross-country flight and being confused by the delighted reactions from other passengers.

“It wasn’t funny to me; it wasn’t dramatic, it wasn’t anything,” Chase tells Biskind. “I thought, ‘Why don’t I just open the door (of the plane) and jump out?’ ”

It was his lawyer, Lloyd Braun — who in the ‘90s became an executive at management company Brillstein-Grey—who first told Chase, “We believe you have a great television series in you.”

Chase wasn’t thrilled with the idea. “My response in my head was, I don’t give a f–k — I hate television.”