Men of the House: Modes of Masculinity in The Godfather

In The Godfather, director Francis Ford Coppola introduces the lead character Michael Corleone in the most curious of ways: almost thirteen minutes after the film has begun, Michael walks into his sister’s extravagant wedding, wearing a full Marines Corps uniform with a non-Italian-American woman on his arm.

This choice on Michael’s part, and on the part of Coppola, signals how The Godfather — though produced in the early 1970s — is a film that reflects on the mid-1940s, a time when masculinity was being redefined in the wake of the Second World War. Historian Corinna Peniston-Bird argues that during the war, “opportunities for contraction, transformation and resistance were limited. Men did not have a choice whether to confirm or reject hegemonic [military] masculinity.” But what happened once the war ended, when men had to use their bodies outside of war? What happened when decorated war heroes like Michael had to come home and redefine their manhood without wartime’s existing framework?

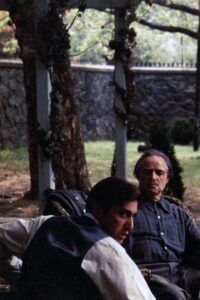

This problem is tackled in The Godfather through Michael but extends to every man in his family. The Godfather dramatizes this crisis of masculinity through male characters’ interactions with other men. While Vito uses restrained movements to exert influence, Sonny’s big, brash, impulsive actions take up space. Michael, meanwhile, takes a page out of both their books, using his intelligence and audacity to command authority. Insofar as the film equates masculinity with power, these important male characters in the film use their bodies in different ways to secure their patriarchal positions at the head of the family.

Vito Corleone controls his movements impeccably, using his body in only the most understated of ways to convey a sense of omnipotent authority over other men. This becomes evident as soon as the movie begins: the first time we as viewers lay eyes on any part of Vito, the camera faces Bonasera from over Vito’s shoulder. Bonasera, sitting on the other side of Vito’s desk, begins to sob at the plight of his daughter’s suffering. We see not a commanding body towering over Bonasera but an out-of-focus hand in the foreground, gesturing to a capo to bring Bonasera a drink in consolation, which he gratefully accepts.

With just the use of one out-of-focus hand, the film situates Vito’s authority in methodical action and institutional relevance. His is a masculinity characterized by the deference and obedience of other powerful men — a masculinity that doesn’t need to exert power actively because the institution he has built on his own terms does it for him. Soon after the camera cuts to face Vito, we see him petting a small cat on his lap as he discusses matters of life or death with Bonasera. The cat, sprawled on his lap, luxuriates in his attention and infuses a playful energy into an otherwise dark and brooding room. Past critics have pointed to the cat as representative of hidden claws under Vito’s subdued façade. To me, however, a subtler detail stands out, particularly when Bonasera makes the grave mistake of asking Vito, “How much shall I pay you?” Vito immediately looks up at him from the corner of his eyes, affronted, and stops playing with the cat. He puts the cat on the table as if to mean serious business, stands up, and calmly confronts Bonasera about his infraction: “Bonasera, Bonasera. What have I done to make you treat me so disrespectfully?”