The aging patriarch of an organized crime dynasty transfers control of his clandestine empire to his reluctant son

A son returns from war and doesn’t want to get mixed up in the family business: organised crime. When his father is gunned down, however, he commits murder and is inextricably bound by ties of blood, heritage and “honour” to a course of vendetta and power ruthlessly maintained through fear. Eventually he inherits his father’s mantle as syndicate big shot and family head, the film ending with a chilling shot of the door closing on his uncomprehending wife as Michael Corleone receives the homage “Godfather”.

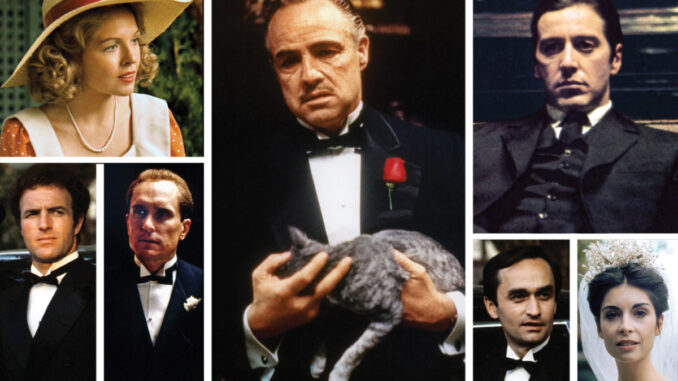

It was the first event movie of the 70s – the one multitudes queued up to see, the one whose dialogue, characters and imagery instantly became ingrained in the collective consciousness. It made stars of Al Pacino and James Caan, and won Oscars for Picture, Screenplay and Marlon Brando, in a triumphant comeback. Shortly after its premiere in 1972, Variety reported, “The Godfather is an historic smash of unprecedented proportions”. At the time the director, Francis Ford Coppola, was holed up in a hotel writing the screenplay for The Great Gatsby, a job he took to relieve his financial problems because he believed in his movie. He had only been given the film after a lengthy wish-list of veterans including Otto Preminger, Elia Kazan, Fred Zinnemann and Franklin Schaffner turned it down. He perked up when Frank Capra wrote to him, claiming it was, ” Out of this world. I cheered inwardly at scene after scene.”

People are still cheering scene after scene in one of the greatest American films ever made, and committing chunks of dialogue to memory — like the goons in TV’s The Sopranos who adore Godfather impersonations, and businessmen like Tom Hanks’ bookseller in You’ve Got Mail who explains to Meg Ryan that The Godfather is the font of all wisdom for the modern man.

Evaluating the story’s irresistibility, Mario Puzo’s best-selling novel was, the author considered modestly, “A great combination, the family story and a crime story. And also I made them out to be good guys, except they committed murder once in a while”. In adapting the book with Puzo, Coppola had a darker, ultimately more profound take: “I looked at it as the story of a king with three sons.” It is pulp fiction turned into opera, an epic of gangster patriarchy, of family, of America itself. “I believe in America,” are the first words in the film, spoken by the undertaker Bonasera, an immigrant proud of his assimilation and enrichment. But, he says, “for justice, we must go to Don Corleone.” Puzo introduced the term ‘godfather’, now synonymous with crime family bosses. The words Mafia, Cosa Nostra, camorra and the like never occur in the film because Paramount producer Al Ruddy was paid a little visit by Joe Colombo, one of the heads of the real ‘five families’, and nervously promised the crime syndicate would be referred to in non-Italian terms.

Ironically, real Mafiosi later embraced the film, paying assiduous court to its principals to this day and affecting the language and style of Vito, Michael, Sonny, their lieutenants and soldiers. Original protests by Italian-Americans who deplored being defamed en masse (the Sons Of Italy, The Italian-American Anti-Defamation League and its champion Frank Sinatra, who raised funds to campaign against the film) have been overshadowed ever since the film’s release by its popularity within that same ethnic group. Italian immigrants’ descendants, whose assimilation and Americanisation has been complete, view with nostalgic yearning the Corleone clan happily pounding down their pasta, celebrating and sorrowing together at the weddings, the baptism, and the inevitable funeral. Such anecdotes, the legends (Brando did stuff his cheeks with cotton, but had resin blobs clipped to his back teeth; Sinatra, universally believed to be the model for crooner Johnny Fontane, did attack Puzo in a restaurant, calling him a “stool-pigeon”), the footnotes (the baby being baptised during the climactic murder binge is Coppola’s infant daughter Sofia), and the postscripts (Brando sending Satcheen Littlefeather to reject his Oscar) are so abundant that there are volumes of Godfather lore and trivia. TV documentaries have been made of the actor’s screen tests.

This landmark remains a masterly work, fully deserving of its reputation. Coppola can be credited with laying the groundwork of 70s cinema with his commanding technical engineering and his audacious, visceral and stately set-pieces – the horse’s head in the bed, the slaughter of Sonny (which Coppola acknowledges was inspired by Arthur Penn’s climax to 1967’s Bonnie And Clyde), the interweaving of the sunny wedding party with Don Corleone’s court indoors, the progress of Michael’s respectful Sicilian courtship of Apollonia contrasted with Connie and Carlo’s explosive domestic life, and, most unforgettably, the dazzling finale of assassinations, carried out against the sacramental rites in which Michael officially assumes the role of godfather. But the film’s finest qualities also reveal Coppola’s fluency in the classics, from the superior pulp of the 30s, into 40s noir and social dramas; his authoritative grip on an ordered, fastidiously constructed narrative, Dean Tavoularis’ richly detailed design, the weight given to a fabulous supporting ensemble (Robert Duvall, Richard Conte, John Cazale, Castellano, Alex Rocco), Gordon Willis’ striking cinematography, Nino Rota’s beautifully melodic score.

The one enduring criticism of The Godfather is that it glorifies the Mafia, affection mingled with abhorrence in its expression of the acts and ethos of Vito Corleone and his extended criminal family. The identification — both Coppola’s and the audience’s —with Pacino’s Michael is unreserved. And cold, ruthless, logical Michael is definitely not the “pretty good guy” it amused Puzo to characterise him as.

Time and two more pictures would highlight the despair and nihilism in The Godfather, with its burden of sins accruing beyond redemption. The 1974 sequel, The Godfather Part II (which took six Oscars, including the only one for Best Picture ever awarded to a sequel) is arguably even more compelling in its elaboration of power’s corruption into complete moral decay. 1990’s flawed Part III sees Michael get his with Shakespearean finality, Heaven finding a way to kill his only joy. The Godfather continues to entice and entrance with its emphatically mythic exploration of family, be it one cursed in blood and ambition.