Iresisted The Sopranos when it started in 1999 because it came out at the same time as Analyse This, the comedy starring Robert De Niro as a mafia boss who enlists the help of a psychiatrist. I honestly thought it was a brazen attempt to create a TV spin-off based on the same premise.

Only when I received the box set of the first series did I realise my error. I watched it in practically a single sitting, pausing only for snacks and toilet breaks, curtains drawn. This was a new mode of binge, longform consumption. This was a new mode of television, one which showed the medium was capable of exceeding cinema. The Sopranos concluded 10 years ago this week, but its legacy in making the so-called small screen huge is permanent.

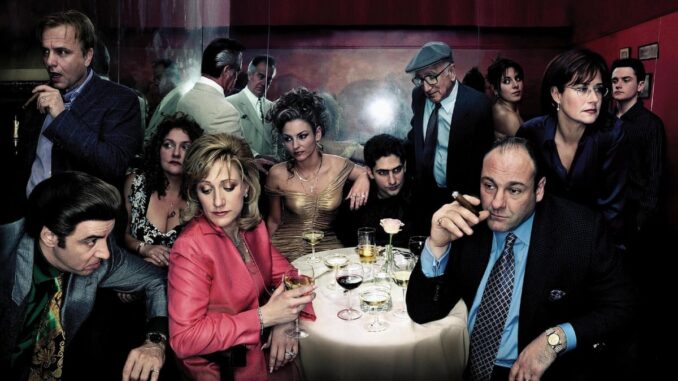

Starring the late James Gandolfini as Tony Soprano, the series showed a hulking New Jersey mobster who was so violently, effectively intimidating that even as a viewer you were nervous of him, felt a strange need to be in his good graces and were flush with relief at the humanity he occasionally exuded. He represented a masculinity that was morally obsolete and yet enviable in the power he was able to wield. Women were his playthings and yet powerful women broke his balls – his ogress of a mother, Livia (Nancy Marchand), like some foul creature who would eat her own children, and who despite Tony’s desperation to please her, co-conspires to have him killed. Then there was wife Carmela (Edie Falco), no Lady Macbeth, apparently not wishing to know all the grisly details of how he provided for his family, but a formidable domestic partner nonetheless. Finally, there was Dr Melfi (Lorraine Bracco), with whom he seeks therapy following a panic attack and in whose sessions his vulnerable sense of supreme male security is exposed and queried.

If The Wire, the only series worthy of being bracketed alongside The Sopranos, reminded of 19th-century novelists like Dickens and Balzac in its extensive depiction of societal layers, then The Sopranos was Shakespearean. Creator David Chase didn’t seek to examine the social and political structures of New Jersey the way The Wire creator David Simon did Baltimore. His creation was of a different order. Tony Soprano is a huge creation, tragic, comic, a man of appalling vice yet solemnly bound by his code, awe-inspiring and deeply flawed, excessively human, inhuman, a giant orb around whom minor but brilliantly conceived characters revolve, including protege Christopher, the ever-sensitive Paulie Walnuts and Silvio, played with deadpan excellence by Steven Van Zandt, aka Bruce Springsteen sidekick Little Steven.

The Sopranos was preceded by the 1990 Martin Scorsese film Goodfellas and features prominent actors from that film including Bracco (Melfi) and Michael Imperioli (Christopher). It also shares its nervous mixture of comic bonhomie and sudden, violent murder, either calculated or out of sheer rage. The Sopranos, too, has a jukebox for a soundtrack, eschewing the emotional prompts of incidental music; it’s as if to say that in these postmodern times, the mafia-as-entertainment is a firmly embedded part of popular culture. The occasional Godfather references are a reminder that the series is conscious of its genre. What’s more, we are implicated as viewers, via Dr Melfi. Her combination of proper moral contempt laced with shameful fascination reflects the viewer’s own ambivalence as we sit in thrall to this series about the everyday doings of very violent men.

The compromised Melfi aside, there are no regular representatives of dogged virtue in The Sopranos, no good cop endeavouring to bring down the bad man. And yet, a strong moral sense lurks at its heart. Take the episode in which Melfi is raped and her assailant walks free. Melfi knows, we know, just say the word to Tony and he would have the asshole squashed like a bug. We can practically hear the temptation in her to do it shrieking as Tony asks what’s the matter with her. We’re shrieking for her to do it. But she resists. Rightly. To have done otherwise would have crossed a line, downgraded the show for a moment of cheap catharsis.

Despite issues unresolved in his domestic life, Tony Soprano prevails against all his foes, ratty irritants like Richie Aprile and his own cousin, Tony Blundetto (played by Steve Buscemi, who also directed the Pine Barrens episode, a Coens-esque, snowbound treasure). But what becomes of him? The series finale, with its abrupt cut to black, has confounded, intrigued and enraged viewers.

David Chase explained it as follows. “The whole show had been about time in a way, and the time allotted on this Earth. Tony was dealing in mortality every day. He was dishing out life and death. He was getting everything he wanted, that guy, but he wasn’t happy. All I wanted to do was present the idea of how short life is and how precious it is. The only way I felt I could do that was to rip it away.” And so, bada-bing, just like a whacking, The Sopranos was done. But the range and capability of TV drama was expanded forever.