Twenty-five years after its debut on HBO, The Sopranos consistently sits at the top of lists of the greatest TV shows of all time. The pressures of being number one was not something that its creator, David Chase, had ever entertained.

A somewhat dour producer/writer (The Rockford Files, Northern Exposure), Chase had inadvertently ascended the ranks to become a sought-after TV talent who nevertheless aspired to a film career. Still, in pitching the concept of a mobster mired in internal conflict, he found an appetite for change amongst the networks he was working for.

With stagnant formats and generalised output, most executives were struggling to find a hit in this brash post-1980s world. But after punting his unconventional “bad guy as protagonist” idea and being repeatedly rejected, Chase found himself walking away from HBO in 1997 with a deal as both writer and director of the pilot.

When the first series got the green light, he set about achieving his vision, without much hope that he would get beyond one season. Adept at subverting the story conventions of the time, Chase had a product that fit the format but raised the game in terms of character development, depth, black humour and, for television, a visually enriching cinematic style. The Sopranos instantly stood out as something bold and innovative.

Reinventing a mafia character to add complexity beyond the achievements of James Cagney, Marlon Brando, Al Pacino and Robert De Niro would be a challenge that James Gandolfini would relish, but which would ultimately take its toll on the actor as he wrestled with the darkness of his character.

Gandolfini: an imperfect anti-hero

Like the character he was to play, James Gandolfini also hailed from New Jersey. He was a character actor with depth, but HBO was initially worried about his leading-man qualities. Even Chase, who had his heart set on Bruce Springsteen’s musician pal Steven van Zandt (who went on to play sidekick Silvio), had to be persuaded.

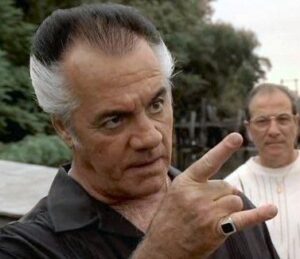

But ultimately, the risk paid off and it was considered iconic casting – Gandolfini’s credibility playing both family man and brutish avenger were vital to the success of both series and character. This bear-like, aggressive tough guy had inner demons and this show was going to share them with you. And Gandolfini was going to make you care.

Fully inhabiting Tony Soprano, Gandolfini brought heart and empathy to the role as did Edie Falco as his long-suffering spouse Carmela, who helped bolster the familial dynamics of discord further. As the seasons rolled on, her role became evermore devastating and enthralling as her character hardened.

Tony was at the forefront of a new wave of lead characters that permitted sympathy for the devil. Here was an audience that wanted fallible, relatable characters, not just straightforward heroes and tough guys.

Relatability is a crucial factor in the show’s iconic status and timeless appeal. It also tapped into a growing trend in the US of talking through psychological problems and mental health in therapy. Tony’s burgeoning awareness of his own mental health problems is the revelatory moment that kicks off the series: a fainting episode that cannot be medically explained sees him prescribed a session with psychiatrist Dr Melfi (Lorraine Bracco).

Creating an imperfect anti-hero at the heart of this mafia family was a stroke of genius. External conflict meets internal conflict, as an alpha male mobster manifests the psychological demons conjured up by a troubled relationship with his ruthless mother, the indomitable Livia. This key relationship was central to Tony’s dilemma and his fate.

In the first episode, Chase established Tony’s character by having him carefully shepherd baby ducks out of his swimming pool. Here was a man who was kind to animals but deadly when betrayed. Audiences were frequently disconcerted watching him execute grisly murders, then head home for dinner with his family.

Episodically, the show pivoted from such violent and bloody action to small familial scenes, forgoing a traditional linear narrative structure for huge emotional arcs that would span whole seasons. With no “story of the day”, no episode could be deemed to have a happy ending – just as Chase wanted it.

A golden age of drama

Subsequently, HBO found itself at the forefront of a new golden age of “cinematic television”. The Sopranos paved the way for new worlds and a wild west of platforms, full of promise and hope. Soon, new voices such as Shonda Rhimes (Grey’s Anatomy, Scandal), Amy Sherman-Palladino (Gilmore Girls, Marvellous Mrs Maisel) and Lena Dunham (Girls) would break through the din of white, male writers to create a broader perspective and elevate sidelined female stories that existed outside the familiar, patriarchal world that Tony inhabited.

Genre-busting series such as Transparent had no need to tiptoe around challenging storylines with ever-evolving, selfish, judgmental, entirely flawed but endearing characters. Similarly, Orange is the New Black, gave us empathetic, engaging backstories to the female prisoners.

Breaking Bad’s Walter White trajectory, from quiet good guy to drug kingpin, would begin its arc a short six months after The Sopranos took its final bow in July 2007. And The Wire continued the evolutionary story from March 2008 with a show that would go on to explore institutional failure, drugs, deprivation and the challenges of urban society.

It’s ultimately impossible to conceive of White, drug-addicted Nurse Jackie, serial killer Dexter or Mad Men lothario Don Draper without the flawed Tony Soprano. And unfathomable that a TV show could have the same impact in today’s streaming panorama, where flawed characters are the norm.

But in a blistering attack recently, David Chase decried the current state of affairs, claiming that thanks to multi-tasking viewers with short attention spans, the 25-year golden age of groundbreaking, taboo-busting TV is well and truly over, and executives are once again risk averse.

Grateful for the quality TV dramas that came after, for many this is what makes The Sopranos the perennial number one.