“Twilight” taught us the dangers of young women not choosing themselves

I think I came to “Twilight” the same way I came to the “Harry Potter” series: kids my friend babysat were reading them. And if the kids were absorbed, reading under blankets with flashlights long after bedtime, exchanging paperbacks in school like covert lunch trades, the books had to be good, right? Soon after I acquired my own library copy of Stephenie Meyer’s first vampire book, that anticipation turned to dread.

Oh no. What were we teaching the children?

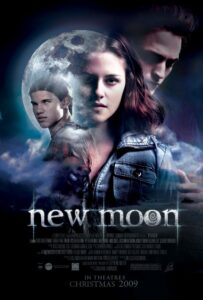

The successful books, a quartet of vampire romance novels aimed at teens, which went on to sell 120 million copies worldwide, soon received the movie treatment. The first film was released in 2008, with sequels yearly until the finale, a two-parter that ended in 2012. “Twilight” was elevated by its stars like Kristen Stewart, Robert Pattinson and Anna Kendrick, and director Catherine Hardwicke gave the first film a moody, rich feeling. It was a decent film, one I enjoyed looking at visually, but its message was troubling.

Hardwicke was dropped from subsequent films. The story grew more worrisome in the books and their adaptations and more ridiculous, the young characters turning from teen love to teen marriage and parenthood. The final film in the story, “The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn – Part 2,” turns a decade old this month and its theme is as terrible as ever. This is what happens when you don’t let young women choose themselves.

If you were not a child or babysitting a child or someone who enjoyed childish fiction in the early 2000s (yes, young adult fiction is and should be wonderful and read by adults, but this isn’t it), let me break it down for you: Bella Swan (Stewart) is a high school student who just transferred to the small, misty town of Forks, Washington when her life is saved by Edward Cullen (Pattinson), a handsome, if pale, mysterious fellow student who lives with his super rich parents and four adopted siblings in a modern mansion in the woods. Bella and Edward fall in love.

Complication? He’s a vampire, as is his found family. Additional complications? Bella is sort of also in love with Jacob (Taylor Lautner), a character who’s Indigenous and additionally a werewolf. Yes, it’s problematic already. But Edward wins, I guess, in that Bella married him when she’s barely 18. She gets pregnant on their honeymoon like poor Lane Kim in “Gilmore Girls.” Spoiler: Bella dies in childbirth but Edward turns her into a vampire and saves her. Also, their kid is a weird human-vamp hybrid, and as such, ages rapidly and for some reason known only to Satan, is rudimentary CGI for a good portion of the movies — possibly the worst artistic decision since that woman tried to restore a 19th-century Jesus fresco.

The story behind the story? Meyer is a practicing and by her own devout account Mormon. It would be difficult not to read her particular faith into this story of teen marriage and teen pregnancy, given both the tale’s anti-abortion leanings and what Meyer herself has said in interviews, like “Unconsciously, I put a lot of my basic beliefs into the story.”

The lovestruck teens (well, Edward is 104 when the story starts) wait to have sex until marriage, which Edward insists on. He might be anxious to settle down, being three decades older than the average life expectancy for an American human, but Bella is actually a teenager. When her mom gets the invitation to the wedding, she’s excited in a way that few parents would be if their 18-year-old were marrying a centenarian. Or marrying anyone at all.

Bella’s going to college is bantered about early as an abstraction. No one is ever serious about it. Neither is she expected to get or interested in getting a job. She has no interests, other than Edward/Jacob. Stewart’s performance brings an intelligence to the role that isn’t really present on the page, and as such, her character feels weirdly disconnected. Won’t she be bored, just zooming about the mansion with no work, no education, no hobbies even? At least Edward plays the piano.