When The Godfather Changed Hollywood Forever?

On March 24, we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the premiere of The Godfather. It was nominated for 11 Oscars, won three, and changed cinema forever. The film, which never uses the word “mafia” or the phrase “cosa nostra,” is renowned as the premiere gangster film of all time, and is more than occasionally called the greatest movie of all time. Yet its follow-up, The Godfather, Part II, is often ranked higher. This has more to do with filmmaking than with crime.

Paramount Pictures released a 4K Ultra HD edition of The Godfather Trilogy on March 22. The scope of the Corleone family saga is the story of 20th Century America. Over the course of the three films, Francis Ford Coppola delivers a multigenerational tale of corruption, vengeance, and family duty. The Godfather elevated mob movies to high art, paving the way for the street-level gangsters of Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets and Goodfellas, the suburban family crimes of The Sopranos, and the original sinners of Boardwalk Empire.

By lifting the former B-movie genre to A-list status, The Godfather had a ripple effect which swept across all of motion pictures. Here are some examples of what the film did to cinematic culture.

It Redefined the Idea of Movie Hype

The Godfather began as one of the most anticipated motion pictures ever put in production, but it wasn’t the first. Casting news for Gone with the Wind, which held the record for highest-earning film for over a quarter of a century, made national headlines in the late 1930s. Paramount optioned Mario Puzo’s manuscript while it was still being written. The studio anticipated a bestseller but, as the book sat on top of The New York Times Best Seller list for 67 weeks, almost dropped plans for a feature length adaptation entirely. They were afraid they wouldn’t live up to expectations.

The bestselling 1969 novel sold over 9 million copies and was deemed to be the hottest property in Hollywood. Everyone wanted to be in or on that picture. Robert Evans, Paramount’s head of production wanted The Godfather to be directed by an Italian-American. The studio’s first choice was Italian legend Sergio Leone, who passed to begin preparations for his own gangster epic, Once Upon a Time in America.

“I got a call from Francis Coppola, a name from the past,” Al Pacino told The New York Times. “First, he says he’s going to be directing The Godfather. I thought, well, he might be going through a mini-breakdown or something. How did they give him The Godfather?”

Before signing Coppola, Paramount approached Peter Bogdanovich, Peter Yates, Richard Brooks, Arthur Penn, Costa-Gavras, Otto Preminger, Elia Kazan, Fred Zinnemann, Franklin J. Schaffner, and Richard Lester, the director of the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night and Help! Still, they ultimately decided on the young director with only a few small budget films, plus the infamous musical flop Finian’s Rainbow under his belt.

“It just seemed so outrageous,” Pacino said. “Here I am, talking to somebody who I think is flipped out. I said, what train am I on? OK. Humor the guy. And he wanted me to do Michael. I thought, OK, I’ll go along with this. I said, yes, Francis, good. You know how they talk to you when you’re slipping? They say, ‘Yes! Of course! Yes!’ But he wasn’t. It was the truth. And then I was given the part.”

First Modern Blockbuster

The Godfather was the highest-grossing film of 1972. For a while, it was the highest-grossing film ever made. It was the first film to earn $1 million a day, and changed the way the motion picture industry did business. It got personal.

The standard studio practice for an anticipated box office hit was to open in one or two theaters each in New York and Los Angeles, and add theaters week-by-week to reach the top 200 markets in about a month. Paramount premiered The Godfather in New York, expanded to 156 theaters in its second week, earning $1.2 million, and then blew up in wide release.

A year later Warner Bros. would follow the strategy in the horror genre. The Exorcist opened the day after Christmas on 30 screens in 24 large-city theaters without previews for critics. It set individual house records, earning $1.9 million. The studio expanded it into wide release faster than a demon child could spew pea soup. This would be perfected two years later, when Universal Pictures opened Jaws on 500 screens across the country.

It Changed the Star System

In the book, Michael is tall and blond, and Paramount wanted Robert Redford or Ryan O’Neal to play the role. Typical, WASP-y leading men of the era. Warren Beatty turned it down. According to “The Masterpiece that Almost Wasn’t” extra included in The Godfather Trilogy, Coppola had to fight to get Pacino cast as the returning World War II hero and college graduate. The studio didn’t want some New York theater actor carrying a movie. They wanted a star, and had plenty of ready-made talent.

The Hollywood star system created stars like Detroit made cars. From the 1920s until the 1960s, studios crafted personas for young actors, sometimes giving them new names and backgrounds, and brought them up through the ranks of box office stardom. After productions like Bonnie and Clyde shifted the cinema landscape, studios began to take chances on fledgling independent filmmakers like Coppola, leading to the 1970s auteur era. Audiences appreciated the new raw talent on the screen.

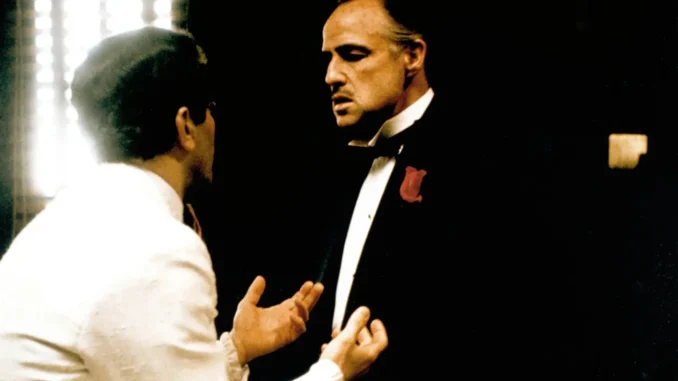

Coppola wanted to make small, personal films, and The Godfather accidentally sparked the Hollywood Renaissance, the most experimental period of film since the silent years. Box office success no longer relied on fabricated recognizability. Much of the change in the hiccup of stardom was due to the rise of Method acting. As Vito Corleone, the don of method acting, Marlon Brando, handed over his title to a new generation. Pacino, Diane Keaton, and Robert De Niro from The Godfather, Part II ruled box office for the rest of the decade and the next one too. Talia Shire would go on to be just as perennially recognizable a face as Adrian in Rocky.

Ultimately the moviemaking machine reasserted itself as studios took all they learned from the Star Wars phenomenon and the show became their business again.

The Numbered, Prestige Sequel

The Godfather set records at the Academy Awards. Brando won the Oscar for Best Actor. Pacino, James Caan and Robert Duvall were all nominated for Best Supporting Actor Oscars. Coppola was nominated for Best Director. He and Puzo won the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar. The movie won the Academy Award for Best Picture. Paramount couldn’t wait for a sequel–which at the time seemed preposterous. Prior to The Godfather, Part II, sequels were at best the province of ongoing light entertainments from the studios, such as The Thin Man movies. More often than that though, they were cheap cash-ins with dwindling creativity, innovation, and talent.

Yet The Godfather, Part II won six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and was the installment that earned Coppola the coveted Best Director Oscar. And some cinephiles believe it is better than the original. It was the first studio sequel with a number in the title. Initially criticized as a cheap exploitive attempt to cash in on a familiar name, it instead created a dynasty.