Why Tracker and Reacher are Peak “Drifterpreneur” TV

“All great literature is one of two stories; a man goes on a journey or a stranger comes to town.” — Leo Tolstoy

Two of today’s hottest shows — Tracker and Reacher — are keeping the tradition of the “traveling stranger” alive and well by providing comfort viewing with a kick.

There has always been room on television for the archetype of the helpful loner traveling from town to town.

In the 1960s, James Garner’s Maverick featured a wisecracking cowboy poker player with a heart of gold.![]()

That show’s campy cousin, The Wild, Wild West, had two Secret Service agents in tight trousers solving cross-country crimes from a swanky steam engine (the original Airstream?).

In the 1970s, The Incredible Hulk put a contemporary spin on the traveling stranger theme, complete with that decade’s anxiety over nuclear power.

The show’s hero, Dr. David Banner (Bill Bixby), was not out on the road for fun and fortune. Instead, he was trying to evade capture and find a cure for his gamma-ray-created medical condition.

Forced to move constantly for his own protection and work odd jobs to survive, he still helped others in need while often putting himself in danger, his only reward being the chance to fight another day.

Despite its sci-fi trappings, The Incredible Hulk is the very definition of a “stranger comes to town” show and proves that the trope transcends genre.

There was even a series of Maxwell House Coffee commercials in the early 1980s that featured a handsome photographer named Hal who traveled the country on foot with his Golden Retriever, Duke, making countless friends and cups of coffee along the way.![]()

This tradition of the traveling loner as reliable audience engagement continues today with the television shows Tracker and Reacher, whose heroes are enigmatic loners with no fixed address but many handy skills.

They are both constantly on the move for Reasons, and help the people they meet more from a sense of justice than a need for cash (although they do accept cash, and Tracker’s Colter Shaw even takes Venmo).

This nod to compensation reflects how most leads of these traveling shows will help the folks they cross paths with by performing good deeds for about an 80-20 split of money and justice.

There is indeed an underlying sense that each of these charismatic drifters would help their troubled new friends out for free, but this is always supported by a transactional framework of either previously agreed upon payment or an indirect surprise “reward” after dispensing justice.

The traveling stranger genre took a more spiritual bent in the 1980s with Michael Landon’s Highway to Heaven, a gentle show about an earthbound angel tasked with performing an unspecified number of good deeds to earn his wings.

This trend continued in the 1990s with Roma Downey’s Touched By An Angel. This show featured a distressingly corporate celestial hierarchy where an angel seeking advancement had to provide heavenly guidance to people facing difficulties.![]()

The notion of “payment” exchanged for good deeds here is less tangible than in the more secular shows mentioned, but it still fulfills the genre’s unspoken transactional requirement.

In most of these shows, however, the freedom of the road cheerfully coexists with a kind of vigilante capitalism that (if you’re lucky!) includes an Airstream.

But seriously, why is this solitary and transient way of life so stubbornly appealing as a television show premise, decade after decade?

How is it not? That is the better question!

It relies on an engaging lead, for sure (see Natasha Lyonne in Poker Face for another example in this category), who also has at least one unique skill or trait.

But beyond that, the “Drifterpreneur” premise is a triumph of (particularly American) wish-fulfillment: a scrappy loner with unique skills starts an all-cash business that offers aid to a revolving cast of interesting people and requires a lot of travel through beautiful rural landscapes.

The very structure of this series premise offers a good deal of freedom in terms of storytelling.

It has a built-in case-of-the-week dynamic anchored by an overarching series mythology or Greater Mystery, allowing individual episodes to spend more time on one aspect or the other.

It is also a great way to bridge the gap between completely linear storytelling (a hallmark of prestige television) and the entirely self-contained episodic structure that was the series standard for decades.

This open-ended storytelling model doesn’t require any homework on the viewer’s part and is baked into both the framework and appeal of traveling stranger shows. Just like its heroes, the audience is always free to go and always encouraged to return.

The established frequent movement from town to town in these shows presents rich possibilities for different guest stars, where the occasional Big Name Actor can slip into the anonymous lineup of that week’s townspeople.

There is also the opportunity for recurring guest stars to play those endearing scamps who are guaranteed to fall back into trouble at some upcoming point on the hero’s travels.

The need for different visual locations presents fantastic options for these shows.

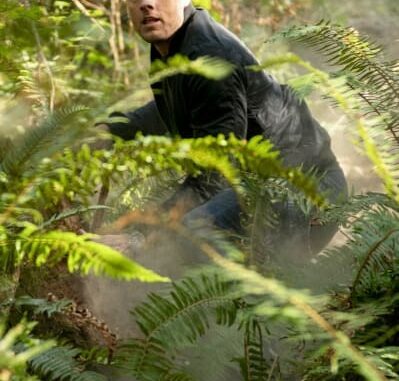

Tracker and Reacher use British Columbia and Ontario, respectively, as stand-ins for their USA settings, but they still convey a sense of rural American grandeur that makes it easy to believe their heroes’ solitary, nomadic lives are possible.

One thing that’s needed out on the road is a reliable mode of transport, giving these shows a chance to express character through choice of vehicle.

Tracker’s Colter Shaw drives a black GMC pickup truck that’s nimble enough for high-speed chases through city streets and strong enough to pull his silver Airstream trailer in quieter moments.

This deftly represents Colter’s reliance on modern tech to perform his job safely (the shiny new pickup) and how he’s literally hitched to his troubled past (the vintage Airstream).

Jack Reacher’s penchant for hitch-hiking and public transportation is the ultimate expression of mobility and self-reliance: when trouble finds him, it usually comes with whatever vehicle he’ll need (often a military helicopter) or the means to borrow one.

Also, these loners aren’t really alone — true solitude requires trusted staff. Reacher has his ex-military found family; Colter has actual family, plus a devoted team of handlers and experts.

This need for social infrastructure presents the opportunity to feature a strong supporting cast that complements the hero’s character while being interesting enough to watch on their own.

Tracker and Reacher may update the traveling stranger tradition with computers and smartphones. Still, one core attraction of these shows that viewers have responded to for decades hasn’t changed: a strong moral component.

Including the more obvious examples of Highway to Heaven and Touched By An Angel, the traveling stranger shows involve relatable ethical quandaries that require a response.

Sometimes, the heroes are slow to follow their better natures, but even those who are whole-hearted do-gooders often have to make a choice.

Tracker’s Colter Shaw could technically stop after performing the letter of his reward assignments when they are worded as just finding information leading to a missing person’s whereabouts, but he’s often emotionally invested enough by that point to continue working the case.

However, he’s got financial and personal responsibilities to his team and family to consider in addition to his own safety and has to at least pause for thought before going ahead and being a hero.

The heroes serve as a moral compass to others, as well. The people they help are often in serious trouble, which will require sacrifice on their part, and they need convincing to take action.

Jack Reacher can usually point to the potential of immediate physical harm, while Colter Shaw presents accurately projected odds of survival.

The heroes dispense gentler advice when the stakes are a little less life-or-death, but it always rests on what each conflicted character — and the viewing audience — knows is the right thing to do.

But perhaps the bulletproof success of traveling stranger shows over the years comes from the one question they all ask: where will the hero go next?

Wherever that is, we’re along for the ride!