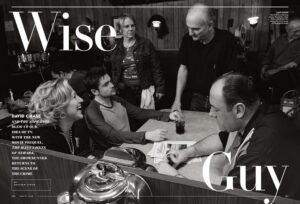

Overflowing with insight; stuffed with revelatory interviews and anecdotes and archival footage; as bursting with flavor as a baked ziti; and as immersive, in its way, as the show itself, “Wise Guy: David Chase and the Sopranos” is Alex Gibney’s sensationally artful and engrossing two-hour-and-40-minute documentary about the greatest show in the history of television.

If you’re a fanatic for “The Sopranos” (and who isn’t?), you probably already know a fair amount about how the show came to be, and “Wise Guy,” for a while, treads familiar ground. The film is framed as a profile of the show’s visionary creator and showrunner, David Chase (the opening credits redo the driving-into-Jersey “Sopranos” credits with Chase in the passenger seat), who is interviewed by Gibney on an exact mock-up of the set of Dr. Melfi’s psychiatrist office, a joke/stunt that recedes into the background yet never loses its playful resonance, since it pings off the way that “The Sopranos,” for Chase, was a kind of therapy. For him, even talking about the show, analyzing its secret sauce, is offered up with a certain gnomic reticence. (Within that, the disarmingly sincere and at times ruthlessly blunt Chase is actually something of an open book.)

Chase, born into an Italian-American family in 1945 and raised in New Jersey, discovered art cinema when he was in college (he says Fellini’s “81/2” blew his mind open, though he didn’t necessarily understand what the film was about), and he was perfectly positioned, by age and temperament, to be one of the New Hollywood upstarts. We see the imitation-Godard student-thesis film he made while at Stanford, and he and his wife, Denise, then moved to Los Angeles, where he tried to break into the film business, with zero success. Chase wrote a horror cheapie called “Grave of the Vampires.” He was then tapped, based on an old spec script, to write an episode of “The Bold Ones” (one of my favorite shows as a kid), which launched him as a TV writer. “The Rockford Files,” “I’ll Fly Away,” “Northern Exposure”: he became a successful power player in the world of the small screen. But every day he worked on those shows, the restrictions of network television made him die inside a little. He couldn’t pretend that those shows expressed his dreams. What everyone he knew told him is that he should try to write a show about his mother.

Chase, haunted by his desire to be a big-screen director, originally conceived “The Sopranos” as a feature film; he wanted it to star Robert De Niro and Anne Bancroft. He then tried to sell it as a TV pilot, but the networks all passed. HBO, however, flush with its new identity as a place that created drama and comedy more close-to-the-bone than anything you could see on network (“The Larry Sanders Show,” “Oz,” “Sex and the City”), was ideally positioned to launch Chase’s vision. The budding cable behemoth, represented here by former chairman Chris Albrecht, actually made a point of suggesting that Chase should shoot the show in New Jersey, even though it would be more expensive. In fact, every single exterior was shot there. (The rest of the series was shot on a soundstage at Silver Cup Studios in Astoria, Queens.) All of this will be familiar to the multitude of “Sopranos” fans who’ve done deep dives into the show’s background.

But then “Wise Guy” starts to capture some of the aspects of “The Sopranos” that maybe only a documentary can — and, in the process, to navigate the show’s inner mysteries. We see montages of the audition process, watching many of the actors who tried out for each role. Chase keeps saying that none of them were right, but most of the auditions are actually quite good. Almost any of the actors could have nailed the roles on network (had the show gone that way).

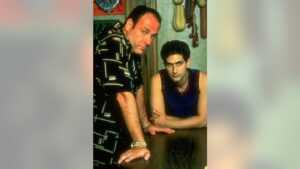

What Chase really means is that they’re doing standard old-school TV acting. Then we see a long-haired Michael Imperioli reading for Christopher, and he has something: a fullness of personality, a quietude so confident that he pops; the role suddenly exists in three dimensions. (Imperioli thought the show was some bargain-basement thing, and figured Chase was a Mob-drama lightweight because of his non-Italian last name.) Lorraine Bracco was the one movie star in the cast, and based on her role in “GoodFellas” she was tapped to play Carmela. But she didn’t want to do that sort of role again. She had her sights set on Dr. Melfi, because Melfi’s wily poker-faced quality would be so different from anything she’d done before, and she wanted the chance to create a new kind of Italian-American woman onscreen.

As for James Gandolfini’s audition, he left all the actors in the dust the way that Brando left the entire studio system in the dust. When Gandolfini reads for the role of Tony, he has a volcanic intelligence, a speed of anger that guarantees that Tony, regardless of how depraved his actions, will always be the smartest, most compelling guy in the room. As for the guilt-tripping, castrating, borderline homicidal Livia Soprano, Chase explains that the character absolutely was his mother. That was a big part of what gave the show its screwily personal dimension.

The template was set, yet “The Sopranos,” in that first season in 1999, would grow deeper and darker. There was a point at which executives at HBO wanted Artie Buco’s wife, Charmaine (Kathrine Narducci), with her ability to see Tony clearly for who he was, to become the show’s “moral center.” That’s classic network thinking. But what was radical about “The Sopranos” — and still is — is that Tony, the gangster we’re asked to identify with, is so far from being a moral center that the audience is prompted, at every moment, to test what it’s rooting for. The HBO brass pushed back against Chase on the famous fifth episode — the one where Tony, driving Meadow around on her college tour, spies a Mob rat who’s been hiding in the Witness Protection Program and takes a detour to strangle him. But this was the show’s revolutionary daring, as bold as anything in ’70s Hollywood. We would now be in cahoots with a monster, obeying a compulsive code of loyalty that rendered his violence as ugly as it was badass. As Chase puts it in the film, every character on the show, even Melfi, has made a deal with the devil. That’s a major part of what kept the drama high-stakes, off-balance, mesmerizing.

Chase got his shot language from ’70s movies too. Instead of the master shot/medium shot/close-up recipe that turns TV into bite-sized visual nuggets, Chase went back to Bertolucci and to “Chinatown,” building the flow of cinema into the show’s DNA. Gibney threads clips from “The Sopranos” throughout the documentary, and does it so deftly that we relive the show in all its hot-wire intimacy, and also reexperience it as the spiritual epic it is. A thousand moments, one journey: Tony’s odyssey of pleasure and peril, guilt and fear, conventionality and anarchy. Chase makes the fascinating point that the medium of television has always been about selling. Part of the revolution of “The Sopranos” is that it flipped the capitalist energy of the small screen on its head, making the show’s drama a deconstruction of the money culture that was coming at us from every angle: Tony’s crimes, the American consumer culture that was now so ramped up it disgusted Tony even as he binged on it.

“Wise Guy” teems with great stories: about how upset Tony Sirico was that he’d have to muss his two-tone hair (which no one was allowed to touch) for the “Pine Barrens” episode; about how Chase decided to cast Steven Van Zandt after seeing him as a presenter at the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame, and how Van Zandt at one point stood a credible chance of landing the role of Tony; how the writers’ room was fueled by hours of shooting the breeze about toxic personal stories, which inevitably made their way onto the show; and how the whacking of any regular character became an offscreen high drama (Lorraine Bracco recalls that if Chase asked to have dinner or lunch with you, it meant you were dead), since that actor would now be out of a job.

And, of course, there are the stories about Gandolfini. He has been a man of conflicting legends, but what emerges here is that he was enormously well-liked by almost everyone who worked on “The Sopranos.” They considered him generous, funny, playful, and devoted. But he had complications. He became notorious for not showing up on set (to the point that HBO would ultimately fine him $100,000 for every day he didn’t show), though when we hear Gandolfini describe the crunched intensity of his work schedule we almost understand his erratic behavior. I would usually never say this about an actor, but it genuinely seems as if tapping into Tony Soprano’s rage, and pushing it further and further the way he did on “The Sopranos,” loosened a screw in Gandolfini. It’s almost as if, in the mania of his superstardom (combined with his fierce privacy), he began to merge with the character.

As Edie Falco points out, there was a child alive inside Tony that was central to what we responded to in him. And maybe that child was alive in Gandolfini as well, a child who threw a tantrum against the world (Gandolfini vented more fury at paparazzi than any actor since Sean Penn), and against his own health (he ignored his doctor’s orders about the food-and-drink intake that would ultimately kill him). Chris Albrecht recalls that he staged an intervention for Gandolfini, and when the actor entered Albrecht’s New York apartment and saw everyone sitting there, he turned around in disgust and walked out, saying to Albrecht, “Fire me!” Gandolfini died in 2013, and we see Chase’s eulogy for him, which is a thing of beauty. One of “Wise Guy’s” most haunting insights is how the entire series — the scripts, the other actors — evolved in tandem with Gandolfini sinking into the life force of Tony’s darkness. He gave the largest performance the small screen has ever seen.

And what of the last episode, and the show’s fateful final moments? The meaning of that cut to black has been debated for 17 years, but David Chase isn’t coming clean, and no one else is either. (The documentary tweaks that with an ending sublime in its wit.) But isn’t it obvious what happened during the final seconds of “The Sopranos”? Tony got whacked. And he didn’t get whacked. Both possibilities loomed, floating in the air — and in that iconic moment, it’s as if both happened at once. Tony died…and he also lived. Just as the show itself ended and, at the same time (as Chase points out in the lyrics to “Don’t Stop Believing”), it went on and on and on. “Wise Guy” is a thrilling testament to how “The Sopranos” changed television forever and, in doing so, changed us.